The Grammar of Creation

Creation as God’s First Textbook

By Theresa Willen, M.Ed.

November 6, 2025

Creation as Curriculum

Before the written Word was given, God authored the created world as a visible text.

The Psalmist’s language of declaration and proclamation is inherently pedagogical: creation does not simply exist—it instructs. The early Church Fathers often referred to the world as the liber naturae, the “book of nature,” complementing the liber scripturae, the book of Scripture. Together, they form a unified revelation—one visible, one verbal—both bearing the imprint of the Logos through whom all things were made (John 1:3).

The pedagogical implication is profound: creation was designed not only for habitation but for formation. It functions as the first classroom in which humanity learns to perceive order, pattern, and meaning. To study creation, rightly ordered, is to study theology in its most elemental form.

Learning to Read the World

To observe creation is to recover the posture of the learner. Observation precedes interpretation; perception precedes analysis. This aligns with the biblical pattern of knowledge → understanding → wisdom (Proverbs 2:6), the triadic rhythm that undergirds Aletheia’s educational philosophy.

Creation invites this same process. Its patterns—the alternation of light and darkness, the symmetry of the human body, the seasons of growth and rest—train the mind to recognize coherence. They model divine order, revealing that truth is not an abstraction but an embodied reality.

Scripture emphasizes continuity:

The world’s teaching is constant, cumulative, and cross-cultural. Whether through the grandeur of galaxies or the precision of photosynthesis, creation declares that divine order undergirds material form.

A theological pedagogy of observation therefore begins not with data collection but with wonder. As G.K. Chesterton observed, “The world will never starve for want of wonders; but only for want of wonder” (Tremendous Trifles, 1909/2014, p. 7). Wonder disciplines perception—it teaches the learner to see rightly, to attend before assuming, to receive before explaining.

The Logic of Divine Order

To interpret creation is to discern its grammar—the structural principles through which God communicates truth. Just as human language depends on syntax, so creation depends on divine order. Every relationship—light and darkness, seed and soil, rest and labor, male and female—reflects the relational coherence of the Creator Himself.

In classical Christian thought, this coherence was understood as participation in divine reason. Augustine wrote that “the whole of creation speaks of God” (Confessions, 1998). In other words, created reality itself is a continuous confession—every finite good bearing witness to the infinite Good from which it flows.

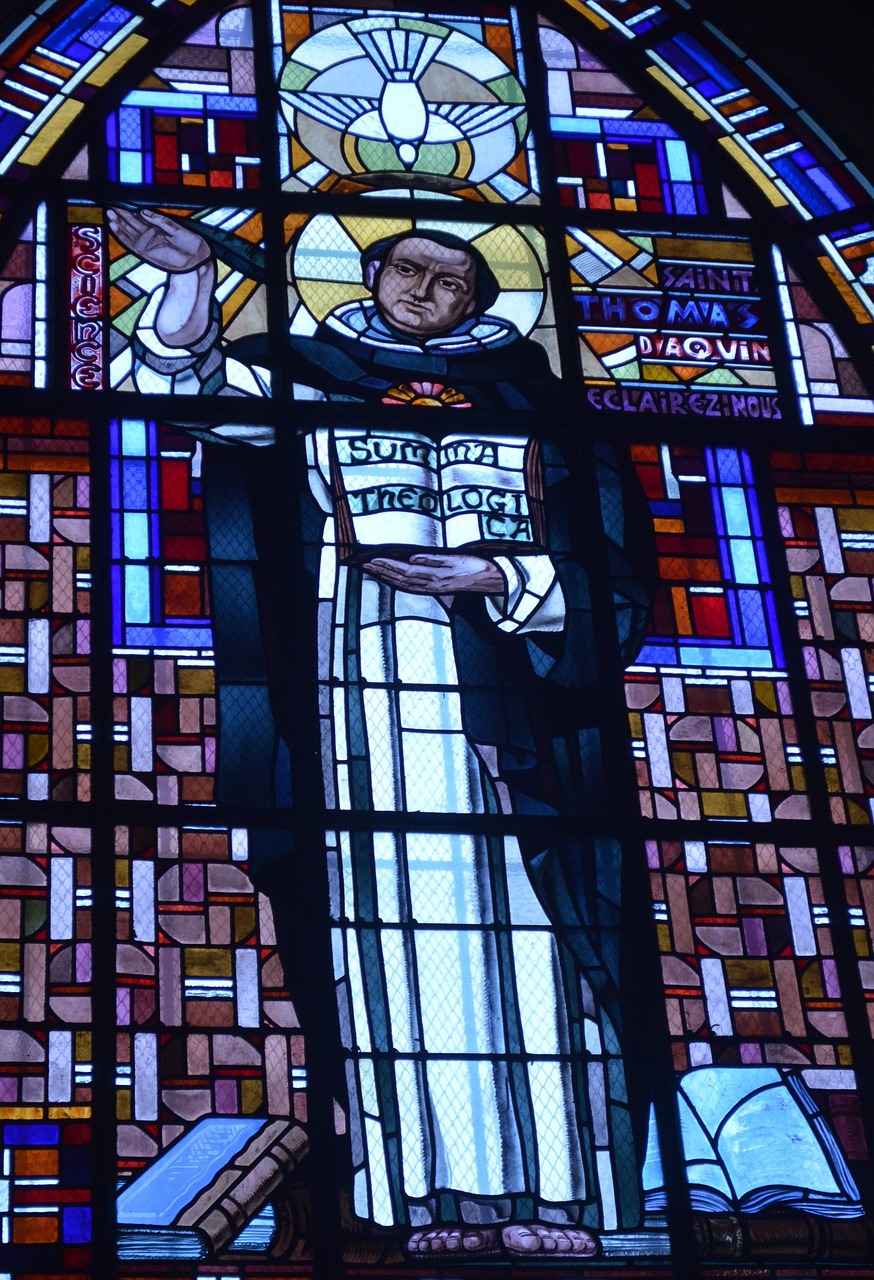

Aquinas later developed this insight, teaching that the laws of nature are expressions of the eternal law, accessible to human reason because they proceed from the rational will of God (Aquinas, 1947). For Aquinas, the study of created order was not merely philosophical; it was participatory—an act of perceiving the divine mind reflected in the structure of reality.

Modernity, however, has increasingly divorced fact from meaning, fragmenting the unity that once characterized both scientific and theological inquiry. The consequence is pedagogical as much as philosophical: education becomes mechanical, not moral; informational, not formational. When order is stripped of its moral and metaphysical grounding, grammar becomes mere structure without significance.

A Theopaideic framework restores coherence. In the Theopaideia model, integration is not simply interdisciplinary—it is theological. Knowledge of the world is ordered toward knowledge of God. The patterns of creation are the scaffolding for wisdom, inviting us to recognize that order itself is revelation.

Reading Creation as Pedagogy

To apply the grammar of creation is to bring human learning into alignment with divine design. This movement—from observation to interpretation to application—translates directly into the practice of Christian education.

Attend to Creation’s Rhythms

The alternation of work and rest, of sowing and harvest, of silence and speech, provides a natural rhythm for formation. Educational environments that honor these rhythms nurture peace, attentiveness, and endurance.

Integrate Knowledge Holistically

Just as creation functions as a unified whole, subjects should not be siloed but interwoven. Literature, science, and history converge where they reveal aspects of the same divine order. Integration is not an innovation—it is obedience to reality.

Cultivate Stewardship and Reverence

The posture of the learner toward creation should mirror that of worship: gratitude and care. To study the created world is to engage with God’s artistry, requiring both intellectual rigor and moral humility.

When students learn to “read” the world as God’s first textbook, they recover a form of literacy that precedes words—the literacy of wonder. They come to see that wisdom does not begin with accumulation, but with attention; not with analysis, but with awe.

Restoring the Coherence of Creation and Curriculum

Christian education must recover this foundational truth: creation teaches. The world’s order is not incidental—it is instructional. Every law of nature and structure of form reflects the character of the One who spoke it into being.

To read creation rightly is therefore to participate in the ongoing revelation of divine wisdom. The heavens still declare. The grammar still holds. When students, teachers, and parents alike learn again to read the world as His text, education becomes what it was always meant to be: a sanctifying journey from knowledge to understanding to wisdom.

References

Augustine. (1998). Confessions (H. Chadwick, Trans.). Oxford University Press. (Original work published ca. 397–400)

Aquinas, T. (1947). Summa Theologica (Fathers of the English Dominican Province, Trans.). Benziger Brothers. (Original work published 1265–1274)

Chesterton, G. K. (2014). Tremendous trifles. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. (Original work published 1909)

Holy Bible, English Standard Version (ESV).